I AM NOT INDIA'S DAUGHTER

Reflections on a banned documentary about the gang rape in my hometown of Delhi

TANVI MISRAMAR 12 2015, 12:00 PM ET

When a child is born in India, it’s customary to give out a celebratory tip (called “bakshish” in Hindi) to the hospital attendants who helped during the birth. When I was born in a Delhi hospital, an elderly relative told my father not to give out too much. It’s not like your baby is a boy, she said.

In Delhi (and I assume in other cosmopolitan Indian cities) this kind of casual misogyny is everywhere. Growing up there, I learned to either tiptoe around it, or call it out and toss it aside with any of the other crap I didn’t subscribe to. While misogyny is hardly exclusive to one country or culture, India bears particularly ghastly symptoms of it. The female body is in real danger there, and the frequency of rapes, infanticides, and domestic violence in the country is impossible to ignore. During my adolescence, many of the city’s public places were dominated by men, and so felt unsafe. Walking through them, I'd brace myself for the stares and lewd comments, which would come irrespective of what I was wearing and regardless of whether I was making eye contact. Still, throughout my childhood, I believed women could do anything, or at the very least, should be afforded the choice to do anything.

In Delhi, casual misogyny is everywhere.

It’s not a particularly uncommon belief among young Indian women today, although women with certain socioeconomic, geographic, and cultural backgrounds might be able to afford that mindset more easily than others. Jyoti Singh came from a poor family, and although I can’t say for sure, it seems from accounts of her life that she pushed past socioeconomic and cultural barriers and strived for more than what society expected of her. In late 2012, the 23-year-old medical student died as a result of a sickening, brutal gang rape on a Delhi bus. I lived in Delhi at the time, and although I heard about rapes frequently on the news there, that incident affected me differently. It seemed less abstract, closer to home. It also confirmed something I had refused to believe all my life, that for a lot of people, women were—I was—not just inferior, but less than human. After mustering up the courage this weekend, I finally watched Leslee Udwin’s much-talked-about film India’s Daughter, a look back at that horrific crime, which premiered in the U.S. this week.

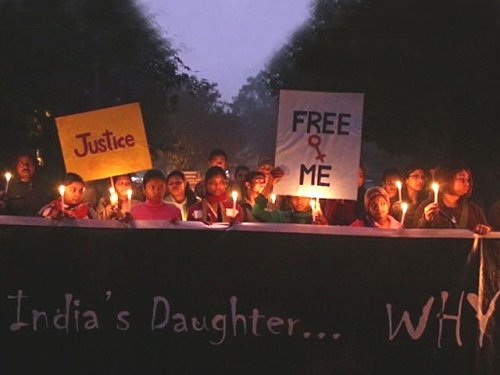

By then the BBC documentary first aired in the U.K. had already stirred up a storm across the ocean in India. Politicians there scurried to ban it before it was due to air on Indian television. Some members of parliament decried the legal and ethical implications of the documentarian’s interviewing the then-accused (now convicted) rapists while court proceedings were still underway. (As Monobina Gupta noted in Caravan, other participants in ongoing court cases have spoken to the media without such concerns being raised.) Others called the film a foreign conspiracy to “defame” India, saying that its release would damage the tourism industry (because of course, gagging the media is a sure-shot way to attract foreign tourists). Some also said the snippets of the interviews released incited further violence against women. But many politicians, feminist leaders, and celebrities opposed the ban. Television channel NDTV suspended its broadcast in protest during the hour the documentary was supposed to air in India.

The ban caused a “Streisand Effect,” leading Indians curious to know what the fuss was about to seek the film on the Internet. This is what Shekhar Gupta, a senior Indian journalist, tweeted on March 5: [click link to see inserted pic]

I live in the United States now, and I also found the film after a quick Google search. As I was watched it, I felt a lot of things: Recognition, revulsion, and vision-blurring anger are some I can name. There were also quieter, sadder feelings too complex to identify clearly. The gruesome details of the rape were not new to me, but it was still difficult to see the rapists rehashing the events of that night. In one scene, Mukesh Singh, one of men convicted of the crime, casually discussed reaching into her, pulling her intestines out.

“You can’t clap with one hand, it takes two hands,” he said in another scene, without flinching, blaming Jyoti for her own death. If she hadn’t fought back, he said, he and the other rapists would have gone easy on her. These sorts of quotes from him—and similarly regressive, even violent, ones from his lawyers—made me want to throw something. Ultimately, people should watch the film if just to understand what inhumanity looks like—how banal it is.

But the film also has flaws. One is the narrow focus on Jyoti Singh’s role as a daughter, which is reflected in the very name of the documentary. Kavita Krishnan, an anti-rape activist interviewed by Udwin, told NPR:

The thing is that we are more than what we are seen as by our parents. There are aspects of our life that we don't talk about with our parents. And I think in seeing her only as a daughter, this film has made a mistake.

She’s right. It is narrow. But so is the perception of women in the country. Even if that’s not something Udwin intentionally wanted to bring out, it’s still, to me, part of what's important about the documentary and the controversy surrounding it.

The film shows Jyoti as an abstract symbol. She is “India’s daughter”—mourned by parents, and appropriated by both a cause and its opposition for their respective agendas. She is split in the imagination of her country. For the rapists and their lawyers, she failed her daughterly duties and bore the consequences. “India’s daughter” is supposed to have guarded her own modesty, which is linked to the prestige of the family. She was supposed to have been virtuous and virginal, protected and defined largely by male relatives. Going to a movie with a strange boy who was not her brother or father—which is what Jyoti had just finished doing when the assault took place—undermined these expectations. A.P. Singh, one of the defense attorneys, openly declared that he would set the women in his family on fire if they engaged in “premarital activities.” Another lawyer, M.L. Sharma, had a penchant for sexist metaphors. “A woman is like a flower,” he said in the documentary. “A flower needs protection—if you put that flower in the gutter, it is spoilt. If you put it in the temple, it is worshipped.”

The other narrative strain in the film was precisely this whole flower-in-a-temple scenario. It talked about how “good” Jyoti was. She was a good daughter (she had asked for her parents’ permission to go out that night), a good student (she worked very hard), and a good friend. In this telling, she was ultimately a martyr—sacrificed to rally a country behind a cause. Her father said in the movie that Jyoti (which means “light” in Hindi) would dispel India’s darkness.

I’m not saying that all these things about Jyoti—that she was a good student and devoted daughter—are untrue. I’m saying that they don’t have to be true for the crime committed against her to be just as heinous. The film shows this “good girl” and “bad girl” rhetoric—“India’s daughter” is either, depending on who’s talking about her—but not much else. In the movie, she’s a 2-dimensional figure. But Jyoti, the person, was probably much, much more when she was alive.

That’s why I am not “India’s daughter.” Yes, I’m the daughter of parents who told that silly old relative in the hospital that it was precisely because I was a girl that they’d be leaving a bigger tip for the hospital attendants. Yes, I’m my brother’s sister. Yes, I’m an Indian woman. I’m also a journalist. A friend. A sexual being. I’m not defined completely by any one of the million pieces of my identity. Like everyone else, I’m extremely flawed, and still expect to be treated equally, fairly, and humanely. Even if I was born a girl.

Full article here -

http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2015/03/i-am-not-indias-daughter/387574/