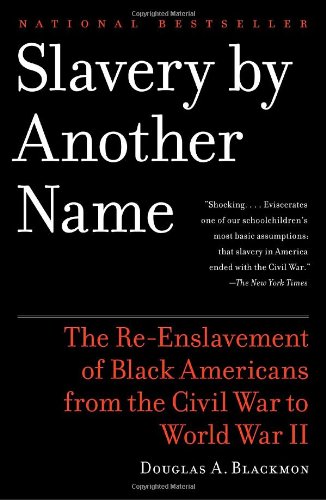

Book Review: Slavery by Another Name by Douglas A. BlackmonBuy this book at Amazon.com

Slavery by Another Name by Douglas A. BlackmonBy Aaron WhiteheadTuesday, April 7, 2009The very premise of Douglas Blackmon's book, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II, is a shock to even the most jaded of history buffs. The idea that African-Americans were held in something very akin to slavery throughout the former cotton belt is a shock. Even more disturbing is the fact that this process continued until World War II. This uncomfortable truth upsets our basic understanding of American history and race relations in the years following the Civil War. As such, the book is a vitally important addition to the historical record.

In the introduction, Blackmon tells us that the book came out of a story he pursued as Atlanta bureau chief of the Wall Street Journal. He uncovered the fact that a number of American companies, including U.S. Steel, profited from what was essentially slave labor at a number of industrial sites throughout the South. This discovery led Blackmon to investigate the untold story of slavery in the years after the Civil War, a story that was missing from the public's understanding of the era.

Blackmon frames most of the book around the Cottenham family. His case study is Green Cottenham, a child of former slaves who got caught in the south's modern form of peonage in the early 20th century. Green came to be re-enslaved in much the same manner as thousands of others across the south. A black person (usually a man) would be accused of some petty crime and brought before a judge. The trial was perfunctory, the defendant had few rights, and the verdict was often predetermined due to graft. Once found guilty, the defendant was fined for the crime and forced to pay the court's fees. Often unable to do so, the defendant became a wage slave. County governments throughout the south used these prisoners as wage slaves or, more often, sold their labor to a local businessman or farmer. These circumstances resulted in a life little different from the slavery that was allegedly eradicated by the 13th Amendment.

Blackmon focuses mainly on Alabama, but he puts forth strong evidence that this form of peonage existed throughout the deep south, affecting more than 100,000 people. This was part of a wider effort on the part of southern whites in the years after the end of Reconstruction to reassert the racial hierarchy of the antebellum years. Blackmon documents the steady loss of political, social and human rights suffered by African-Americans in the years following 1876. The Jim Crow laws, the Black Codes and the terrorism of the Ku Klux Klan have been well-documented by other sources, but Blackmon reveals a new degree of subjugation. The knowledge that they could be taken before a biased judge and returned to slavery for a minor offense — if, in fact, any offense had been committed — played a large part in producing a sense of terror among southern blacks that helped "keep them in their place," through the calculated efforts of powerful whites.

If Blackmon does approach the subject in a roundabout way, he at least succeeds in making a number of very important historical points, attempting to fill the gaps in the historical record and especially to correct commonly held misconceptions about the period in question. He goes into great detail about how the events of these years were either whitewashed out of the history books or explained away as somehow neccessary. This interpretation of the period survived in history books for over 100 years and still refuses to go away. The most common myth is that the period after emancipation resulted in a great lawlessness among freed slaves. It was also alleged that when blacks went into state and federal government, there resulted a great lawlessness and chaos. This "justified" their removal from public life as well as their disenfranchisement. This influential myth is best illustrated in the captivating and horrifying film The Birth of a Nation.

Blackmon exposes these myths as constructs by the white establishment to justify their own racism and to exculpate those who profited from slave labor. He takes a close look at the historical record and finds little evidence of widespread black lawlessness. More dangerous, in fact, were the white vigilante groups — of which the Klan was just one — who roamed the South in the years after the Civil War. In fact, the number of arrests correlated strongly with the demand for labor from industrial and agricultural operatives. When you also consider that the vast majority of charges were for vaguely defined crimes such as "vagrancy," it becomes clear that law and justice were all but irrelevant to the process. When slave labor was needed, blacks were rounded up to fill the need.

Blackmon dug through old records in many courthouse basements to prove that the widespread imprisonment of blacks — which led to their being sold off as slave labor — was due to a corrupt system. State and county governments made a great deal of money selling off convicts, and their financial interest in arresting more blacks resulted in the false arrests and perfunctory trials that sent black men to work. Working conditions were abysmal. Even official state inspectors, who were by no means racially progressive, kept condemning the conditions in which the "convicts" were kept. Blackmon goes into detail to describe the despicable way of life at Slope No. 12 of the Tennessee Iron and Railroad Co. (which later became a subsidiary of U.S. Steel). Death tolls were quite high as prisoners worked under dangerous conditions in the mines. Death, disease, sexual assault and occupational hazards were a matter of course. It was here that Green Cottenham, around whom Blackmon bases part of his narrative, met his untimely death.

Despite the importance of the subject matter and the shocking revelations, the way in which Blackmon describes hearing these similar stories over and over again becomes redundant. This broad approach gives us a sense of the widespread nature of the problem, but it also means reading the same narrative retold many times, with only names and locations changed. It seems that the book would have been improved either by a) broadening the approach to a society-wide study of the issues, or b) focusing on a detailed account of just one area of the problem, rather than similar detailed accounts of several different regions.

For all the book's problems, it is still a necessary read for those interested in the historical period, postwar southern society or African-American issues. Blackmon does a good job of making these facts relevant, revealing to naive whites why many southern blacks still fear and distrust the police and the legal system. At the time, the victims of this system of peonage pleaded for help from the local, state and federal government, as well as appealing to outsiders for assistance. No help was forthcoming.

Not only were the southern whites and their lawmakers actively rolling back the Constitutional guarantees of southern blacks, they were helped by the apathy of the northerners. After fighting the Civil War and dealing with the messy issue of Reconstruction for ten years, most northern whites were tired of enforcing racial equality in the South. By 1876, they were content to abandon the freed slaves to their former masters. There were exceptions; President Theodore Roosevelt set about challenging the system by prosecuting slaveholders in Alabama, but was forced to retreat on the issue due to the violent backlash by southern whites, as well as the growing realization that the problem was much bigger than he was prepared to deal with. Eventually even he, like so many presidents before and since, gave up the struggle for civil rights in return for southern political cooperation. This federal deal with the devil would survive until Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act in 1964.

But the most interesting point in the book is raised by Blackmon in the introduction. He says that when he revealed his findings to white people, they expressed their dismay but were not really shocked. Many saw it cynically, as though they already expected the worst of southern whites. Troublingly, other whites — while admitting that the story was unfortunate — saw it as almost inevitable; the expected outcome considering the times....

Full review:

http://blogcritics.org/book-review-slavery-by-another-name/What Emancipation Didn’t Stop After All By JANET MASLINPublished: April 10, 2008

In “Slavery by Another Name” Douglas A. Blackmon eviscerates one of our schoolchildren’s most basic assumptions: that slavery in America ended with the Civil War. Mr. Blackmon unearths shocking evidence that the practice persisted well into the 20th century. And he is not simply referring to the virtual bondage of black sharecroppers unable to extricate themselves economically from farming.

He describes free men and women forced into industrial servitude, bound by chains, faced with subhuman living conditions and subject to physical torture. That plight was horrific. But until 1951, it was not outside the law.

All it took was anything remotely resembling a crime. Bastardy, gambling, changing employers without permission, false pretense, “selling cotton after sunset”: these were all grounds for arrest in rural Alabama by 1890. And as Mr. Blackmon explains in describing incident after incident, an arrest could mean a steep fine. If the accused could not pay this debt, he or she might be imprisoned.

Alabama was among the Southern states that profitably leased convicts to private businesses. As the book illustrates, arrest rates and the labor needs of local businesses could conveniently be made to dovetail.

For the coal, lumber, turpentine, brick, steel and other interests described here, a steady stream of workers amounted to a cheap source of fuel. And the welfare of such workers was not the companies’ concern. So in the case of John Clarke, convicted of “gaming” on April 11, 1903, a 10-day stint in the Sloss-Sheffield mine in Coalburg, Ala., could erase his fine. But it would take an additional 104 days for him to pay fees to the sheriff, county clerk and witnesses who appeared at his trial.

In any case, Mr. Clarke survived for only one month and three days in this captivity. The cause of his death was said to be falling rock. At least another 2,500 men were incarcerated in Alabama labor camps at that time....

Full review:

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/10/books/10masl.html?_r=0