The original URL of this page is: www.africaspeaks.com/stephen_rwangyezi/page_2.html |

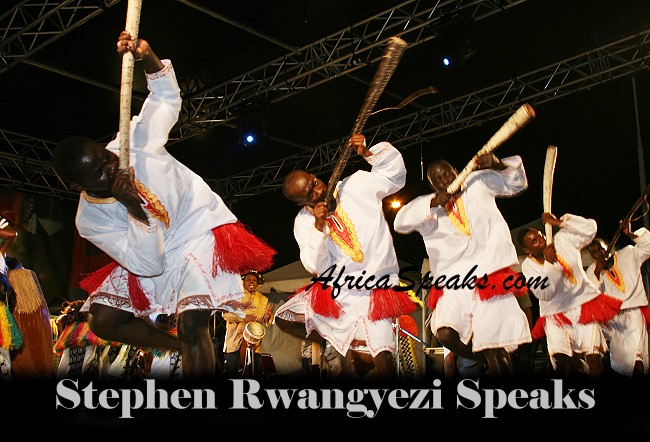

Stephen Rwangyezi Speaks on African IssuesAfricaSpeaks.com and TriniView.comInterview Date: August 05, 2008 Posted: September 05, 2008 Pages: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 RAS TYEHIMBA: We are here with Mr. Stephen Rwangyezi and his daughter Ritah Rwangyezi, members of the Ndere National Dance Troupe. Tell us about the dance group. RWANGYEZI: First of all the word 'ndere' means a flute. The flute was chosen as a symbol of very good music but also as the only instrument I know which is found in all cultures in the world. Just like the red blood that runs in the bodies of all of us no matter our external differences, a flute is a sign that all human beings can enjoy basically the same things. The point we wanted to make when we used it as a name is why discriminate since we are all fundamentally the same? I formed the group in 1984 and there were three reasons why I did that: One, since the times of colonialism in Uganda there was consistent effort to downgrade African culture and cultural values and activities to the extent that we were always taught in school and church that if you want to go to Heaven you play the piano, you play the violin, you sing the halleluiah chorus then for sure you are going to Heaven, and if you play African drums and African dance and music it's a one way ticket to Hell. That was an effort to make Africans feel like second-rate human beings and not be confident and proud of themselves and I think that's partly the reason why Africa has not grown. If people cannot treasure and value themselves as being useful and great then they can't go into the international market and negotiate and they can't go into politics and put policies that they are proud of. So I wanted to bring back this music to glory. I grew up seeing this dance and music only performed at night when people thought nobody was looking. You were always ashamed of it. How could it grow since you are being in a situation where there was no light? There was no electricity so you weren't not doing it for anybody. I wanted to bring it to light. I wanted to put it on stage. I wanted it to move from being ordinary community arts performed for the individual, for self, and bring it to the stage. The second reason was that most people who I have worked with are not only talented but they are also from the disadvantaged part of our communities. Some of them have lost parents, others are from poor families. So I wanted to make them use their own talent and achieve their other personal goals and ambitions especially by taking them back to ordinary schools and enabling them to go to courses to elect their own wishes. The third reason was the use of this music and dance as a means of public education. Uganda has now almost thirty million people but only one percent of this population use electricity in their homes. That means that things like radio, television, let alone internet are not accessible. So how would these people get information on things like HIV/AIDS, environment and all these things? Traditionally, although African communities didn't read or write in the Western sense, education was always transmitted through stories, through riddle, song and dance. So I decided to give it a step further by creating the kind of community theatre that would have important messages and then perform to the communities in the open fields. The other reason which was not the original purpose but which came in later was Uganda, when we started especially interacting with the international communities we realized that Uganda was only known for bad things like Idi Amin. So we wanted to say, "Just a minute! There is more to Uganda than just disaster." RAS TYEHIMBA: How has your programme been received by the Ugandan public? RWANGYEZI: When we started, the first show we did had only three people. That was our chairman, his wife and our guest of honour basically because the community didn't think that these were good arts. But twenty-four years down the line we have two regular shows a week at our centre and they are always full. If you go to any public functions, whether they are private or official, they cannot be finished until there have been cultural performances. As you can see, the President of the Republic of Uganda sent us to Trinidad and Tobago. He could have sent ambassadors and ministers, he could have sent a trade exhibition, but he sent the Ndere Troupe which means that the reputation of traditional music and dance has grown by leaps and bounds. RAS TYEHIMBA: What I especially liked about your performance is your use of traditional African instruments and your explaining that the first guitar, the first violin and many other instruments came from Africa. RWANGYEZI: Which is true, and it's not only the first guitar or the first violin but it's also the musical forms. If you go worldwide and you listen to Blues, to Rap, to Jazz it's all hailing from Africa. The only difference is that, of course, from the days of slave trade and slavery through colonialism, the rest of the world did everything possible to prevent the growth of this music. But they took the same music and developed it into other forms. They took the same instruments and the same sound qualities and developed them into other forms and they started claiming them as their own. What we have been doing is saying, "Well thank you very much." These instruments are there and these musical forms are there. But it might be as well that you get to the roots of it and probably get to the playing styles of the people who developed and have lived with these instruments for so long and be able to enrich the world. What has been happening is a kind of uniformization of styles and music. If you go to America, Britain or anywhere, whoever plays in a symphony plays in the same style. But bringing in these so-called primitive styles and instruments is kind of breathing a fresh air into the musical and dance scene. RAS TYEHIMBA: I also liked how you used song and dance to explain various African traditions, morals and principles. RWANGYEZI: You see, many times I go to performances and I am asked the question, "What are you? A dancer, a singer, a choreographer, a dramatist, a drummer, a playwright?" All I tell them is, "I am an African." What that means is that we in Africa didn't compartmentalize these things. We didn't put them in boxes. When we play an instrument, we sing. When we sing it's a story. When we tell story and sing, we dance. When we do these, we act. Life in Africa is wholesome. It's not about who knows how to do what. You cannot be able to drive a point home. As I told you, the method of knowledge transmission is through music and dance and story telling. You can not be able to drive home a message if you approach it from one angle. Education in the Western sense is in a classroom. You get a child from home, isolate this child from the life at home, take him to a classroom, lock him up and start stuffing him with what you have planned for that day only. In less than forty minutes you think you have sufficiently given to this child. But these kids sitting with you at this time have got different interests, have got different abilities of learning. Some of them receive knowledge through sense of touch, others feel, others listening and others visual. You now bring them to a classroom and lock them up and just shout at them and you think you are a wonderful teacher. In Africa we don't structure learning. We leave it wholesome. When I talk to you, I act to you, I sing to you, I dance. So whichever sense brings this knowledge to you better and faster you still achieve. If we are more than one it's even worse because two or three or five or ten of us receive knowledge differently. So any person who is in charge of imparting knowledge, if you are a good one you should be able to exploit different methods. Putting the dances into context using stories, using songs, using demonstrations and using subtle acting is just part and parcel of African life. RAS TYEHIMBA: What are you trying to convey? What messages are you trying to share when you perform or when you tell a story or when you dance? RWANGYEZI: The central goal is confidence building. The central goal is to say, "Just a minute, I may be Black but I am equally human and there is nothing fundamentally wrong with my genetic make up." Therefore the values that make me who I am, one, two, three, ten, I express them in this way, I convey them in this way and that makes the world beautiful. Even God, if we all believe religiously, when He was making the world He never made it flat. There are mountains, valleys, flowers, snow and different things. There are tall people, there are short ones, black, yellow, pink, green, I don't know what. When we buy clothes we never buy the same colour. Even if we are twin brothers we still end up being a little different. The central message is as an African I have got a contribution to make to the global village. I have got what makes me, me. This is the message I want to bring across for people to appreciate. Not that we are starting a new round of racism but that difference is worth. Pages: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |